Remarks as Prepared for Delivery

Edward J. DeMarco, Acting Director

Federal Housing Finance Agency

The Brookings Institution

Washington, D.C.

April 10, 2012

I. Introduction

Good morning. It is an honor to be here today.

Over the past six years many efforts have been launched by the federal government to stem the losses arising from the housing crisis and to keep people in their homes. Some programs have worked better than others, but almost all of them required trial and error, and were more difficult to actually implement than many had expected.

As conservator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Finance Agency has been deeply involved in many of these efforts, and we have seen our share of successes and missteps. Today we find ourselves in the midst of a national debate regarding mortgage principal forgiveness: Would homeowners, the housing market, and the taxpayer be best served by providing outright forgiveness of mortgage debt for certain homeowners who currently owe more on their mortgage than their house is worth today?

I am grateful to the Brookings Institution for this opportunity to offer some perspectives on this debate and to provide some preliminary findings from FHFA’s most recent analysis of this issue. I will not be announcing any conclusions today—our work is not yet complete—but in view of the state of the public policy debate on this subject, I am pleased to have this venue to enhance the public understanding of this difficult question and to explain how FHFA has approached the matter. The Brookings Institution’s reputation as a home for thoughtful policy analysis and debate of challenging public policy questions makes this a most appropriate setting for this endeavor.

Typically when I begin a speech about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or the Enterprises as I will refer to them, I set the context by reviewing FHFA’s legal responsibilities as conservator. I do so because I believe it is essential for people to understand that Congress considered the objectives it wanted FHFA to pursue as conservator. These objectives may not be easy to meet but they are clear—FHFA’s job is to preserve and conserve the assets of the Enterprises and, in their current state that translates directly into minimizing taxpayer losses. We are also charged with ensuring stability and liquidity in housing financing and maximizing assistance to homeowners.

Today however, I want to set the context for my remarks in a different way—I would like to begin with a few words on the human element of this housing crisis.

Throughout this crisis each of us know of, or have heard about, many individual stories of homes lost through foreclosure. One cannot help but have sympathy for those who have suffered such misfortune. And surely no one can look at the dislocations in the housing market and not feel frustration at how so many people and institutions failed us, whether through incompetence, indifference, or outright greed or fraud. Yet we are also blessed in this country with people and institutions who care, who are strongly motivated to provide assistance and find solutions.

The staff at FHFA has worked tirelessly since the Enterprises were placed into conservatorships to seek meaningful, effective responses to the housing crises. With the staffs at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, Department of the Treasury and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and numerous financial services companies, FHFA staff has sought to develop and improve on loan modification and loan refinance programs that bring meaningful options to struggling borrowers who want to stay in their homes. In a moment, I will describe these efforts and their progress to date. We know we have much more to do and the strategic plan for conservatorship that we submitted to Congress in February identifies that work as one of our three strategic goals.

There is another human element in this story that does not seem to receive much attention. Clearly, many households got over-extended financially. Some accumulated debts they couldn’t afford when hours or wages were cut or jobs were lost. Others withdrew equity from their homes as house prices soared. Others bought houses at the peak of the market, often with little money down, perhaps in the belief house prices would continue to climb. Yet there are other Americans who did not do these things. There are families that did not move up to that larger house because they weren’t comfortable taking the risk. Perhaps they had to save for college or retirement, and did not want to invest that much in housing. And there are people working multiple jobs, or cutting back on the family budget in many ways, to continue making their mortgage payments through these tough times. Many of these families are themselves underwater on their mortgage, even though they may have made a sizeable down payment.

Whichever of these categories any particular homeowner falls into, the decline in house prices over the last few years has reduced the housing wealth of all homeowners. The Federal Reserve has estimated that from the end of 2005 through 2011, the decline in housing wealth to be $7.0 trillion.

Six years into this housing downturn, the losses persist. The debate continues about how we as a society are going to allocate the losses that remain. Asking hard questions in this debate does not make one unfeeling about the personal plight this situation has created for so many. Indeed, the majority of those most hurt by this housing crisis did nothing wrong—they were playing by the rules but they have been the victims of timing or circumstance or poor judgment.

In short, the human element in this unfortunate episode in our country’s economic history stands out and commands our attention. Virtually every homeowner in the country has suffered a loss. But that doesn’t make the answers any easier. And it poses a deep responsibility on policymakers to weigh all these factors in seeking solutions, including the long-term impact on mortgage rates and credit availability of the actions we take today.

With that as backdrop, my goal today is to answer two questions:

- What do the Enterprises do to assist borrowers through these troubled times in housing? and

- How has FHFA assessed principal forgiveness as an option for assisting troubled borrowers?

II. The Enterprises’ Borrower Assistance and Foreclosure Prevention Efforts

Some critics have concluded that FHFA’s refusal to allow principal forgiveness raises questions as to the agency’s and the Enterprises’ commitment to helping borrowers stay in their home. To put the principal forgiveness discussion in context, I think it is useful to start by reviewing the Enterprises’ current borrower assistance programs. The Enterprises have an array of foreclosure prevention programs for borrowers that are delinquent or in imminent default, most of which allow the troubled borrower to stay in their home. For those who are current on their mortgage, refinance opportunities allow borrowers to lower their monthly payment or shorten the term of their mortgage. The primary focus of the Enterprises’ foreclosure prevention programs is on providing borrowers the opportunity to obtain an affordable mortgage payment for borrowers who have the ability and willingness to make a monthly mortgage payment.

a. Foreclosure Prevention Efforts – Home Retention Options

i. Loan Modifications

The Enterprises’ current loan modification programs are designed to help homeowners who are in default, and those who are at imminent risk of default.

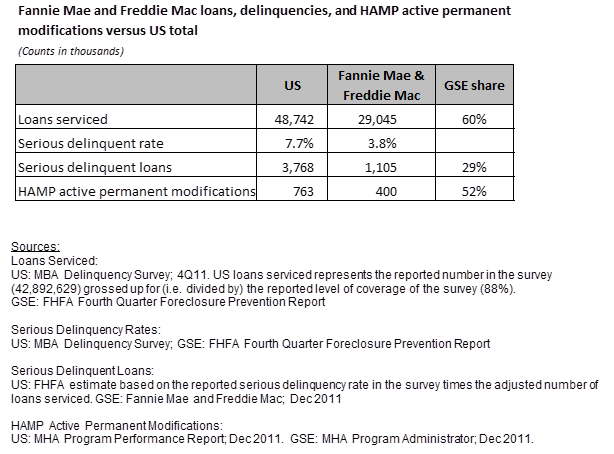

Figure 1.

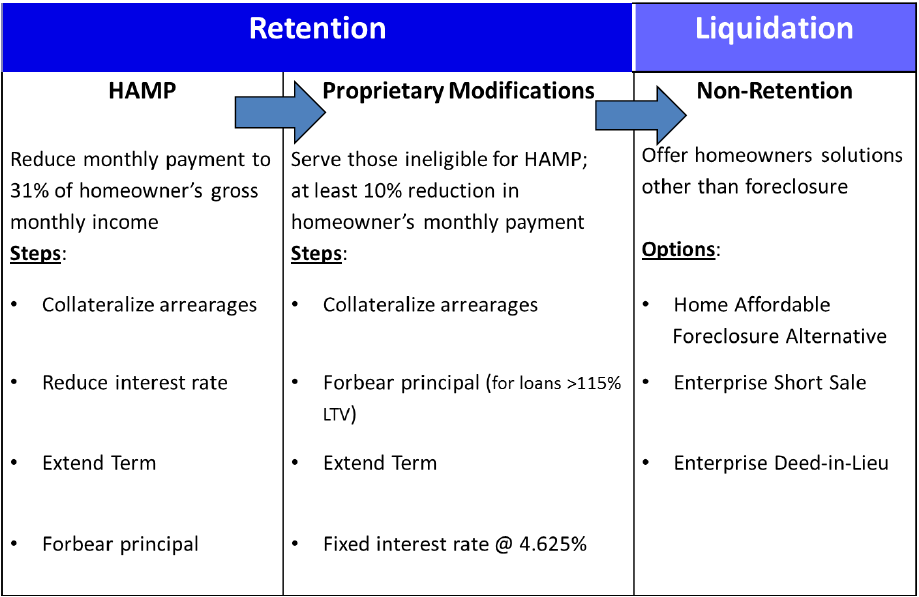

The first modification program the Enterprises use to evaluate a borrower is the Administration’s Home Affordable Modification Program, or HAMP. Under HAMP, an affordable payment is achieved by taking specified sequential steps (or waterfall), as needed, in order to bring a troubled borrower’s monthly payment down to 31 percent of their gross monthly income. Specifically, servicers:

- Capitalize the arrearages, including accrued interest and escrow advances.

- Reduce the interest rate in increments of 1/8th to get as close as possible to 31 percent of the homeowner’s gross monthly income with the lowest possible interest rate set at 2 percent.

If reducing the interest rate does not achieve an affordable monthly payment, servicers then:

- Extend the term and re-amortize the mortgage by up to 480 months (40 years).

If reducing the interest rate and extending the term does not achieve an affordable monthly payment, servicers then:

- Provide principal forbearance down to 100 percent of the property’s current market value or as much as 30 percent of the unpaid principal, whichever is greater.

With a principal forbearance modification, a portion of the loan is set aside. The homeowner does not pay interest on that portion of the loan. Principal forbearance should not be confused with payment forbearance. Under a payment forbearance plan, a homeowner receives a temporary reduction or suspension of payments on the mortgage. This approach is often used to address unemployment or other temporary problems that a borrower may be experiencing.

Principal forbearance has become an important part of loan modifications for underwater borrowers, increasing from 11 percent of total modifications in 2010 to 26 percent in 2011. It means the lender allows the homeowner to defer payment of a portion of the principal of their loan until they sell their home or refinance their loan, and pay no interest on the deferred principal. This approach allows the Enterprises to reduce borrowers’ monthly payments while avoiding principal write-offs. Interestingly, this is the same approach used in many other government-guaranteed loan programs, including the FHA program.

Principal forbearance operates in a manner very similar to shared appreciation, except that with forbearance the investor’s share of any appreciation from the current home value is paid first and is capped at the time of loan modification to the amount of forborne principal. If house prices rise above the forborne amount the borrower captures all the appreciation. Furthermore, principal forbearance does not require any infrastructure changes for lenders and investors to account for future assets and liabilities, as does shared appreciation.

If a borrower does not qualify for a HAMP modification, the Enterprises then look to employ a proprietary modification (sometimes referred to as a "standard modification"). The features of a proprietary modification are also applied sequentially for loans above 115 percent LTV and include:

- Capitalizing the arrearage, including accrued interest and escrow advances.

- Providing principal forbearance down to 115 percent of the property’s current value or as much as 30 percent of the unpaid principal balance, whichever is less.

- Setting the interest rate to a fixed rate mortgage, currently at 4.625 percent.

- Extending the term to 480 months (40 years)

After calculating the modified payment terms, the mortgage loan must result in at least a 10 percent reduction in the homeowner’s principal and interest payment.

Acknowledging the benefit of this approach, the Treasury Department recently announced a Tier 2 program under HAMP that mirrors the Enterprises’ proprietary modification program.

ii. Temporary Assistance

A loan modification is not the best solution for every troubled borrower. For someone who loses their job, has had a medical emergency, or faces some other short-term issue, a loan modification

may not be the best solution. In such cases, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac offer payment forbearance plans that allow a borrower to make no or partial payments for a period of time. The Enterprises also offer repayment plans for borrowers who fall temporarily behind on their mortgage and just need to be given an opportunity to get caught up and back on track. Since the start of the conservatorships, the two companies have entered into more than 660,000 such plans with borrowers.

b. Foreclosure Prevention Efforts – Non-Retention Options

Most troubled borrowers should qualify for a home retention option if they have the ability and desire to stay in their home. If the borrower does not want to remain in their home, or has experienced a permanent and significant loss of income that makes continued home ownership infeasible, the servicer is obligated to consider the borrower for the Administration’s Home Affordable Foreclosure Alternative Program (HAFA), which includes short sale, deed-in-lieu, or deed-for-lease options. For borrowers ineligible for HAFA, the Enterprises employ a proprietary short sale, deed-in-lieu, or deed-for-lease options. Of these, short sales are the most common. In a short sale under HAFA or its own program, an Enterprise agrees to allow the borrower to sell their home in an arm’s-length market transaction and accept the proceeds as payment of the debt. Importantly, the unpaid balance becomes forgiven principal to the borrower. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have completed more than 300,000 such home forfeiture actions since conservatorship.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s instructions to mortgage servicers are clear: only after all these home retention and home forfeiture options have been exhausted should a servicer pursue foreclosure.

c. Foreclosure Prevention Programs – Results

While mortgages owned by other financial institutions or held in private label mortgage-backed securities have a much higher delinquency rate than those owned or guaranteed by the Enterprises, the Enterprises have been leading national foreclosure prevention efforts. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac own or guarantee 60 percent of mortgages outstanding but they account for only 29 percent of seriously delinquent loans (loans where the homeowner has missed at least 3 or more payments or is in foreclosure).

Table 1

Even though other market participants hold 71 percent of seriously delinquent loans, the Enterprises account for more than half of all HAMP permanent modifications. Between HAMP and their own proprietary loan modifications, the Enterprises have completed 1.1 million loan modifications since the fourth quarter of 2008.

Not only are the Enterprises leading efforts in completing loan modifications, as shown in Table 2, the performance of their loan modifications has been better than most other market participants.

Table 2

Re-Default Rates for Portfolio Loans and Loans Serviced for Other

(60 or More Days Delinquent)*

Investor Loan Type | 3 Months After Modification | 6 Months After Modification | 9 Months After Modification | 12 Months After Modification |

Fannie Mae | 11.7% | 18.8% | 24.1% | 27.5% |

Freddie Mac | 11.3% | 18.1% | 23.2% | 26.8% |

Government- Guaranteed | 17.2% | 34.6% | 44.2% | 49.2% |

Private | 23.5% |

Corinne Russell (202) 649-3032 / Stefanie Johnson (202) 649-3030 |