This blog post examines energy transition risk in the housing market and its potential impacts on the housing market’s energy sustainability efforts. Energy transition risk can be defined as risk related to the process of adjustment towards a low-carbon economy.[1] As society moves away from carbon-intensive practices, there is likely to be increased demand for property owners to retrofit their properties to incorporate more energy efficiency features, increase electrification of buildings, and adapt to the changing mix of available energy sources. Effectively managing this transition involves identifying and understanding emerging trends in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and energy efficiency, as well as incorporating the upfront costs of energy efficiency investments.

Common energy efficiency upgrades include improvements to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems; they also include solar panel installation and purchase of energy-efficient appliances. Heat pumps, high-performance insulation, and passive heating and lighting design are all options for property owners. These investments can substantially lower energy consumption and increase property values, reducing costs for a homeowner or tenant over time. These investments may also provide the added benefit of an improved quality of life for the resident. In many cases, however, they may require significant upfront costs. While some government incentives are available to reduce the upfront cost of energy improvements, not all residents will be able to afford such improvements. Further, renters generally do not have the autonomy to make these decisions as for these households — including lower-income households — decisions regarding energy improvements are at the discretion of their landlords.

Scenario Considerations

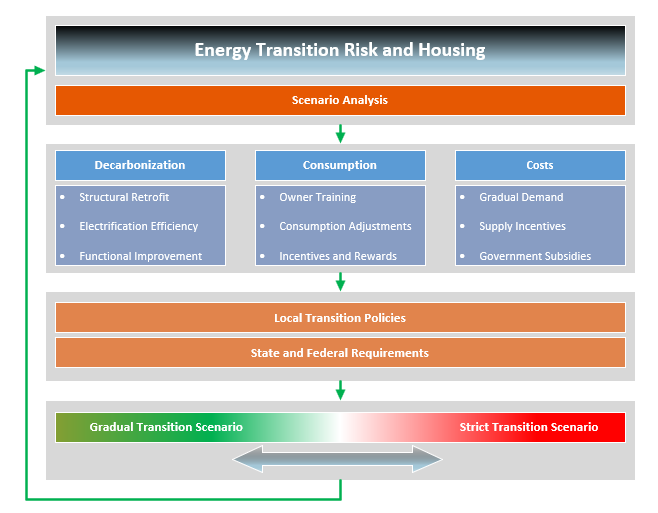

Energy transition risks impact the housing sector through three main channels: building decarbonization, building energy consumption, and costs. As Figure 1 illustrates, decarbonization includes retrofitting, energy efficiency, and functional improvements such as enhanced insulation and weatherization. Energy consumption may be impacted by resident or owner training, incentives, or awards. Finally, costs may be impacted by changes to supply and demand, as well as government policy.

Transition scenario analysis requires identifying the degree to which policy shifts may change energy consumption patterns and how those shifts may impact costs for property owners. Scenario analysis is an important tool to understand the cost of decarbonization and its impacts on the housing sector. Many components of the energy transition are mandated by local ordinances, but they can intersect with related state and federal mandates. Figure 1 shows how the three components of the energy transition funnel through emerging regulatory and policy efforts, creating a range of gradual to strict scenarios for consideration.

Figure 1: Energy Transition Risk and Housing

Under gradual transition scenarios, the rollout of local regulations may be slow, with some localities adopting requirements with longer time horizons for meaningful incentives for energy efficient upgrades. Stricter scenarios could include simultaneous local, state, and/or federal regulations, penalties for noncompliance, or rapid adoption requirements.

Net Zero 2050, often considered a strict transition scenario, assumes that global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050 through stringent climate policies and innovation, including a 45 percent reduction in GHG emissions by 2030. This scenario can be used to estimate the cost of low-carbon retrofits for single-family and multifamily property owners, along with the impact of these costs on loan performance and credit. The costs of transitioning the housing sector to a low-carbon economy could depend on local, state, and national policies, technology development, and property owner preferences. Property owners may encounter mandates that involve significant upfront costs, or they might benefit from financial incentives such as subsidized financing, tax credits, or grants.

Local, State, and Federal Regulatory Examples

In this blog post, we examine several local policies targeting housing sector decarbonization in the United States. This is a nascent area for policy development, and many emerging policy efforts could be considered in a similar scenario analysis.

One example is New York City’s Local Law 97, which impacts multifamily housing. Local Law 97 requires energy system updates in commercial real estate buildings, including multifamily properties. Under the strict Local Law 97 guidance, owners of large commercial real estate buildings are required to meet new energy efficiency and GHG emission limits beginning in 2024, with progressive limits that target a 40 percent reduction in citywide building emissions by 2030.[2]

Other jurisdictions have created similar regulations and laws. For example, Seattle’s Building Emissions Performance Standard (BEPS) aims for a 27 percent reduction in building emissions by 2050. BEPS compliance sets carbon-emission targets that buildings meet over time, with targeted five-year reporting intervals. Buildings that provide low-income housing are provided a gradual compliance window, with longer time to meet these targets.[3]

In California, the Zero-Emission Space and Water Heater Standards are expected to reduce GHG emissions from buildings. These standards, part of California's climate strategy outlined in its 2022 Scoping Plan, aim to help the state achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. These standards will require new installations of zero-emission appliances, such as electric heat pumps, with strict requirements by 2030 for newly constructed residential and commercial buildings.[4]

Boulder, Colorado, is targeting net-zero emissions by 2035 through regulations that affect both single-family and multifamily properties and promoting investments in energy-efficient technologies. Its regulations require strict standards for efficient insulation, HVAC systems, lighting, and overall building efficiency. The regulations emphasize the need for using energy-efficient materials and technologies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions for new construction and major renovations within the city.[5]

At the federal level, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Energy set strict energy efficiency requirements for appliances through the ENERGY STAR® program. Federal agencies also require building codes to promote energy savings in residential and commercial buildings. These federal regulations interact with emerging local policies, potentially incenting homeowners to invest in energy-efficient technologies.

Regulatory Path and Implementation Challenges

Policy changes – locally, and at other jurisdiction levels – may include strict emissions standards, carbon pricing, or energy efficiency mandates. In some cases, these policies can lead to increased compliance costs or the need for significant capital investments to meet the new standards.

At the same time, the energy transition carries opportunities. Amann, Tolentino, and York’s (2023) Toward More Equitable Energy Efficiency Programs for Underserved Households report addresses this duality in making energy efficiency programs more accessible to underserved populations. While these programs offer significant benefits, such as reduced energy costs and improved home comfort, they often do not effectively reach low-income households. Continued research on this gap would be valuable to understand how to mitigate high upfront costs associated with certain energy efficiency upgrades, especially when they disproportionately benefit those who can afford the initial investment as opposed to more vulnerable communities.

Furthermore, the transition to a low-carbon economy also involves significant technology risk. The Financial Stability Board’s (2017) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures Final Report discusses how the transition to a low-carbon economy will require the deployment of new technologies, which can disrupt existing business models and infrastructure. Property owners may need to invest in new equipment and appliances. Those who neglect to update the properties could see them become obsolete, making an eventual transition more difficult.

Considering other countries’ experiences and efforts may help accelerate energy efficiency improvements. The European Union has established consistent and strict energy efficiency standards across its member countries through regulations like the European Commission’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. The United Kingdom has gradually implemented the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard. Both have the goal of promoting reduced energy demand, renewable energy usage, and manageable costs (Carlin, Arshad, & Baker, 2023). These considerations are valuable in assessing transition risks in the housing market.

Conclusion

The energy transition brings both challenges and opportunities for the housing market. Although energy-efficiency upgrades and retrofits involve upfront costs, lifetime savings and reduced emissions benefit residents. Ultimately, managing transition risks involves numerous considerations, including but not limited to consumer sentiment, regulatory compliance, costs, and technological advancements. Other important factors include operational efficiency, market expectations, long-term sustainability, and stakeholder engagement. Considering all of these elements can lead to more effective strategies for navigating the transition.

Responsibilities of the Climate Risk Assessing Exposure to Climate Change Working Group:

- Develop expertise on climate-related risk analysis including the underlying data and methodology.

- Perform outreach to other stakeholders in this space.

- Build capacity for the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) to run climate-related scenario analysis.

[1] See https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/climate-risks-and-opportunities-defined

[2] For details on New York City’s Local Law 97, see: https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/ll97-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reductions.page

[3] For details on Seattle’s Building Emissions Performance Standard, see: https://www.seattle.gov/environment/climate-change/buildings-and-energy/building-emissions-performance-standard/beps-policy-development

[4] For details on the Zero-Emission Space and Water Heater Standards, see: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/zero-emission-space-and-water-heater-standards

[5]For details on Boulder, CO’s Energy Conservation Code, see: https://bouldercolorado.gov/services/energy-conservation-code

References

Amann, J., Tolentino, C., & York, D. (2023). Toward more equitable energy efficiency programs for underserved households. American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/B2301.pdf

California Air Resources Board. (n.d.). Zero-emission space and water heater standards. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/zero-emission-space-and-water-heater-standards

Carlin, D., Arshad, M., & Baker, K. (2023). Climate risks in the real estate sector. United Nations Environment Programme

City of Boulder. (n.d.). Energy conservation code. https://bouldercolorado.gov/services/energy-conservation-code

European Commission. (n.d.). Energy performance of buildings directive. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en

EPA. (n.d.). Climate Risks and Opportunities. https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/climate-risks-and-opportunities-defined

Financial Stability Board. (2017). Final report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf

NYC Sustainable Buildings. (n.d.). Local Law 97. https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/ll97-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reductions.page

Seattle.gov. (n.d.). Seattle building emissions performance standard policy development. https://www.seattle.gov/environment/climate-change/buildings-and-energy/building-emissions-performance-standard/beps-policy-development