Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the economic and regulatory environments have undergone profound changes. Banks[1] encountered major shifts to household savings behavior and now face stricter capital and liquidity requirements. This blog explores three stylized facts examined in a recent working paper, which uses a theoretical model to shed light on how banks adjusted their balance sheets in response to these developments during the decade following the crisis. The insights discussed here can provide a perspective for thinking about potential bank behavior during the current economic cycle.

The Surge in Cash Holdings on Bank Balance Sheets

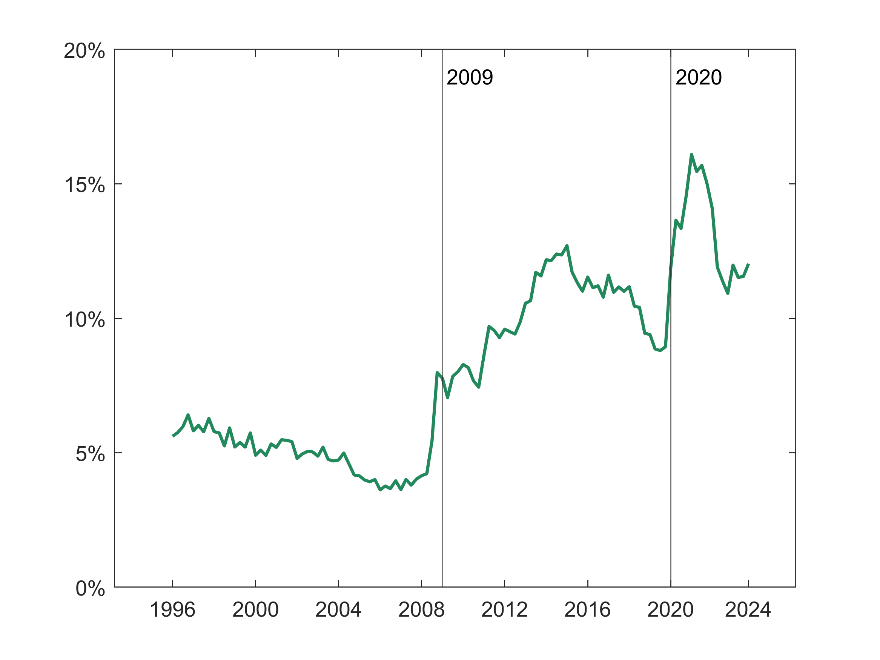

A striking trend following the financial crisis is the increase in cash holdings by banks. Figure 1 shows a steady rise in the proportion of cash in total assets held by FDIC-insured depository institutions, jumping from below 5% pre-crisis, to around 12% from 2009 to around 2016 (what we will refer to here as the immediate post-crisis period), and upwards of 15% during the recent pandemic in 2020. This trend reflects behavioral shifts among households and regulatory changes.

Figure 1: Cash of Depository Institutions

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Quarterly Banking Profile.

Stricter liquidity regulations introduced after 2008, such as the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), required banks to hold more high-quality liquid assets, including cash, to survive short-term funding stresses. This rule, coupled with higher capital requirements, is an important reason why banks shifted away from riskier, less liquid assets, such as loans, and increasingly towards cash reserves in the immediate post-crisis period.

At the same time, households have increasingly sought safe, liquid deposit options, especially during periods of economic uncertainty, such as after the 2008 crisis and during the pandemic. One result of the model in the paper is that banks responded to the influx of deposits in the immediate post-crisis period by increasing their cash holdings.

The trend of higher cash holdings can be viewed as a sign of greater financial sector resilience, but it also raises questions about the impact on broader economic activity if banks simply accumulate cash at the expense of lending when faced with greater demand for deposits.

Decline in Mortgage Lending

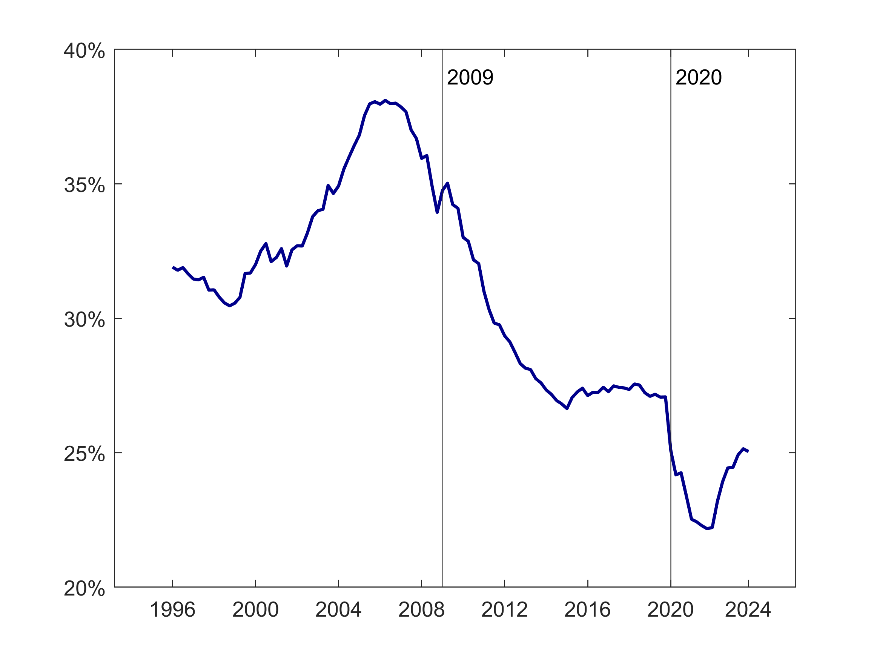

At the same time that the share of cash on bank balance sheets has been growing, Figure 2 reveals that the share of mortgage lending has been on the decline. Before the 2008 crisis, loans secured by real estate—particularly residential mortgages—were a substantial 30% - 40% of bank assets. However, this share began to drop sharply after the crisis, and the downward trend has persisted through to 2023.

Figure 2: Loans Secured by Real Estate

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Quarterly Banking Profile.

Why did mortgage lending decrease despite historically low interest rates in the immediate post-crisis period? The model highlights that a combination of regulatory and economic factors explains the trend. When interest rates drop towards zero during monetary easing, the spread between the return on mortgages or other loans and liquid assets like cash widens, making lending relatively more attractive. However, banks face a trade-off between lending and holding cash reserves when managing their compliance risks. Since mortgages generally reduce a bank’s capital and liquidity coverage ratios relative to minimum required levels, the additional return derived from loans over lower yielding cash must be weighed against the risk of noncompliance that comes with smaller capital or liquidity buffers. Stricter regulation can discourage banks from growing their mortgage portfolios.

On the other hand, expanded government presence in the mortgage market in the immediate post-crisis period and greater household demand for deposits relaxed some of the regulatory pressures on the banks. Counterfactual analyses in the paper suggest that increased supply of mortgages resulting from the larger government presence reduced interest rates on mortgage loans, which spurred greater demand for loans from households. Stronger deposit demand reduces the funding costs for loans, so banks would be encouraged to supply more mortgages, all else equal. Indeed, the model suggests that the proportion of mortgage loans in banks’ total assets would have contracted by more than twice the actual post-crisis change without the shifts in household deposit demand.

Declines in mortgage lending have significant implications for prospective homeowners. Reduced lending may limit the availability of credit, particularly for first-time buyers or those with lower credit scores, potentially dragging down homeownership rates and dampening economic activity in housing markets.

With the finalization of Basel III regulations on the horizon in the U.S., it is useful to consider what countervailing factors are present, from the household or other areas of the economy, that may potentially offset the effects of tighter bank regulations, and their net effects.

The Role of Household Deposit Demand

Figure 3 showcases the net outcome of the rise in cash ratios and decline in mortgage ratios stemming from the interaction of household deposit behavior, regulation, and other macroeconomic factors discussed above. Specifically, from pre-2008 to the immediate post-crisis period from 2008 to 2016, leverage fell precipitously from around 11% to 9% of equity, where it remained until 2020.

Figure 3: Leverage of Depository Institutions

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Quarterly Banking Profile.

The paper pieces together this connection: household preferences for liquidity directly influences banks’ decisions. When households hold more deposits, banks respond by either lending or holding more cash, or finding other safe and liquid investments. The interplay between household savings behavior and banking regulation is crucial—had household demand for deposits not surged, the study suggests the post-crisis shift away from mortgages towards cash would have been much larger. Without heightened demand for deposits, the paper’s counterfactual analysis suggests that the decline in bank leverage would have been even steeper.

The change in household portfolios has broad implications. While cash strengthens bank balance sheets in terms of liquidity, it can also create a paradox: as households save more in the form of deposits, banks that do not have sufficiently high capital buffers reduce lending, particularly in sectors like housing. This trend may hinder economic activity by reducing the availability of credit, especially when combined with low interest rates and tight regulatory controls.

Conclusion: Bank Balance Sheets Moving Forward

The research findings highlight how after the 2008 global financial crisis, subsequent regulations, monetary policy, and changing household behaviors fundamentally altered balance sheets. Banks shifted to holding more cash and issuing fewer loans. While the focus on cash makes the banking system more resilient to shocks, if this behavior persists, it can present challenges for sectors, like housing, that rely heavily on access to credit.

As regulators continue to implement measures, like Basel III, and central banks around the world consider further monetary easing, understanding the delicate balance between financial stability and economic growth will be crucial. This paper provides a simple starting point to think about these issues.

[1] We define banks as FDIC-insured institutions, encompassing national and state banks, federal savings associations, and thrifts (all subject to Basel III capital rules).

By: Vivian Wong

Senior Economist

Division of Bank Regulation

By: William M. Doerner

Supervisory Economist

Division of Research and Statistics

By: Michael J. Seiler

Visiting Scholar

Division of Research and Statistics

Tagged: Research; FHFA Stats Blog; Source: FHFA; Banking; Mortgage Deb